Why do sanctions have no visible effect on the Putin regime? Can the Western, and in fact, already global sanctions put an end to the dictatorship in the Russian Federation? No, known precedents show that such an effect is unattainable. The dictatorships in Cuba, Iran and North Korea have existed for decades under a strict embargo, and they seem to be doing just fine. One should bear in mind that dictatorial regimes are generally much more stable politically than democratic regimes, which are prone to turbulence caused by economic problems, corruption scandals or fluctuations in public opinion.

And yet, economic sanctions are an effective method of weakening the enemy. They cannot force the regime to give up internal terror—on the contrary, they rather provoke its escalation. They, however, seriously curtail the possibilities for external aggression, which requires a large expenditure of resources. So, the regime is forced to pupate, switching from the accumulation of power and expansion to the sole task of maintaining internal stability.

The problem is that, in the case of Putin's Russia, economic sanctions turn out to be double-edged, hurting their initiators. For all its backwardness, Russia has been quite tightly integrated into the world economy as a key energy supplier, a prominent food manufacturer, an exporter of capital, and a large sales market for foreign companies.

Restricting the economic cooperation with a pariah country boomerangs back at the sanctioning countries, reducing the number of jobs, business profitability, household incomes and tax revenues. Since, as noted above, democratic regimes are inherently less stable, these factors can cause public discontent, which may transform into protest voting.

This is why Western governments usually resort to stifling sanctions, which is the least effective way of action. Amid the global economic boom of 2014-2020, it was easy for the West to keep ties with Russia at a minimum, while avoiding the negative social impact and reducing political risks to zero. At the same time, the accompanying populist rhetoric (“Punish the Aggressor!”) quite satisfied the Western public, creating the illusion that the measures taken were achieving their goal.

As the events of February 2022 showed, not only had the Putin regime not abandoned the expansion of the “Russian world,” it escalated the conflict with the West (an ultimatum for NATO to crawl back to the borders of 1997), and unleashed a conventional warfare with Ukraine. The stifling sanctions did not work, revealing their imitation nature; the policy of appeasement failed. This predetermined the transition to the strategy of crippling sanctions—first of all, the rejection of Russian energy products, designed to undermine the economic basis of Putin's petrocratic dictatorship.

But now, the global community is faced with the problem of a negative effect for countries that have abandoned Russian oil and gas. A way out of the gridlock could be finer tuning of the sanctions program. First of all, the measures should be aimed not at sectors (sectoral sanctions), but at the most vulnerable points of the criminal oligarchic regime, neutralizing specific key functionaries and forcing powerful figures to cease active support of the Kremlin. In this case, the threat of inevitable punishment would have a greater effect than the current collective and symbolic “penalties.”

@blackmark_en – in Russian

Follow us:

Telegram in Russian

Telegram in English

Facebook in Russian

Facebook in English

Instagram in Russian

Instagram in English

For example, the current sanctioning has zero educational effect on government-owned corporations. You cannot frighten a government corporation by loss of profits, since all its losses will be compensated from the Russian budget. Moreover, the corporation managements will use the sanctions as an excuse to demand more government support. For private companies, on the other hand, the risk that sanctions may cut them off from both technology and sales markets is a serious argument for abandoning loyalty to the ruling regime. Ideally, Russian business should perceive Putin, his regime and aggressive foreign policy as the main threat to its existence. Private companies should be forced to engage in various anti-government activities such as boycott, sabotage, cross-border relocation of personnel (this primarily applies to the IT sector) and capital, financing protest activities of civil and political activists, etc.

Sectoral sanctions lead to the development of a besieged fortress mentality, making the economic elite rally around the leader, leaving the personnel of the affected companies hostage to the situation and reinforcing the propaganda clichés about the “naturally Russo-phobic West” in the minds of public.

Unfortunately, the Western public tends to see sectoral sanctions as most resolute and uncompromising steps to curb the aggressor, whereas in fact they are purely populist and nominal. For example, an oil embargo by the US, that buys about 3 percent of Russian oil and oil products, will have little effect on Russian suppliers, especially since Washington leaves loopholes for itself so that the supplies would continue, or turns a blind eye to gray import schemes for sanctioned goods. For Europe, however, refusing Russian energy is simply unrealistic, since quick replacement is impossible. The current situation forces the West to continue the bankrupt policy of appeasement, at the same time theatrically expanding imitative sanctions to include, say, Kremlin propagandists and middle-rank officials, most of whom have neither real estate nor financial assets abroad.

Kremlin sensitive points

As we said, the way out lies in focused strikes at the most vulnerable points of the Putin regime. To do this right, it is necessary to understand the essence and the principles of internal organization of the regime. Today's political elite in Russia is essentially a criminal syndicate that has taken full control of the government apparatus. As they say, all countries have their own mafia, and only in Russia the mafia has its own country. This is not the case of the criminalization of elites through their ossification and corruption—this is the case of criminal bosses coming to power and introducing their criminal community code to the governmental power and the economy.

The goal of the ruling elite is personal enrichment through the appropriation of other people's labor and property. The methods for achieving this goal are adequate. This explains, for example, the practice of career promotion of those loyal to the criminal boss, the control over the gang members through mutual cover-up, joint participation in crimes, and the inability to leave the syndicate of one's own free will. The Russian power elite strictly follow the principles of criminal conspiracy, trying not to advertise their fabulous riches and strictly avoiding any formal involvement in fully transparent business structures.

As tradition demands, the income of the ruling criminal group is accumulated in the so-called “collective funds” (in Russian “obshchaks”). An obshchak is a fund designed to launder and legalize criminal capital and to serve a secret disposal of money by the bosses. The administrator of the obshchak is usually a confidant of the boss. He is the nominal owner of the capital, acting in the interests of his sovereign.

Collective funds can be organized differently—they can be banks, investment funds, offshore companies, or charitable organizations to which controlled businesses pay tribute. Top leadership of Russia accumulate and legalize their criminal proceeds using large corporations headed by nominal oligarchs. These figureheads are characterized by political sterility and the desire to keep a low profile to hide their connection with the collective fund beneficiaries.

It is obvious that pinpoint strikes directed at the collective funds would be the most painful for the ruling criminal regime in Russia. That would block their access to the accumulated capital, and paralyze the business structures that launder criminal proceeds. Such retaliatory blows, if systemic, could critically undermine the legitimacy of Putin's government in the eyes of the bureaucracy, since the latter would lose its main motive to partake in the criminal activities of the Kremlin. This would significantly reduce the agency of the government apparatus. Also, such events would most seriously demotivate private business from dealing with the government, making it a toxic partner to work with inside Russia as well as outside.

The largest collective fund of a criminal community in Russia, and possibly the whole world, is known as the vertically integrated oil company (VIOC) Surgutneftegaz. At the end of 2021, at least $56 billion was held on its bank deposits alone, which is more than 20 percent of the revenue part of the entire Russian Federation budget.

Having no debt and not investing in acquisitions, the company purposefully stores currency in bank accounts, which is atypical for any private company. Absurdly, the capitalization of the asset (1.7 trillion rubles at the end of 2021) is 2.5 times lower than its funds on deposits. The financial reserves of Surgutneftegaz, or the “piggy box” as the press calls it, exceed the gold and foreign exchange reserves of countries such as Argentina ($54 billion), South Africa ($49 billion), Australia ($48 billion) or Romania ($44 billion). At the end of 2016, the company kept over 90 percent of this money in US dollars; in the next year's report, it classified its investment structure.

The banks that hold Surgutneftegaz’s deposits are also secret. At the end of 2012, 40 percent of the funds were placed with Sberbank, and the rest—with VTB, Gazprombank, and the Russian subsidiary of the Italian Unicredit. But since then, Surgutneftegaz has not published information about its counterparties. Gazprombank disclosed the company's accounts in its financial statements only because Surgutneftegaz accounted for more than 10% of its liabilities to customers.

For comparison, the world's largest drug cartel, Sinaloa, is believed to have an annual cash flow of $3 billion. Surgutneftegaz's revenue is about seven times higher—which means the collective fund is replenished by $1.5-3 billion annually. Today, the owner of Surgutneftegaz is unquestionably the richest person in the world. The fortune of the officially largest multibillionaire Elon Musk, which Forbes estimated at $219 billion, is still a fortune "on paper". No one has $56 billion cash in bank accounts, not even the Saudi royal family.

The Kremlin owner of Surgutneftegaz

So, who owns Surgutneftegaz? An analysis of open sources alone allows us to say with certainty that the beneficiary of this collective fund is Russian dictator Vladimir Putin himself. Moreover, he acquired control over a significant part of the oil & gas corporation back in the 1990s, even before he started his work for the Kremlin.

Serious business media and analysts are skeptical about the version that the man of the Kremlin is the shadow owner of oil assets worth tens of billions of dollars. The reason for this is ordinary fear, because the only time when someone stuck their nose into the affairs of Surgutneftegaz for real ended in the murder of the troublemaker, which we will discuss in more detail later. But the very fact that business circles and the blogosphere have actively discussed Putin's affiliation with the company for over a decade requires at least some explanation. As Russians like to say, there is no smoke without fire.

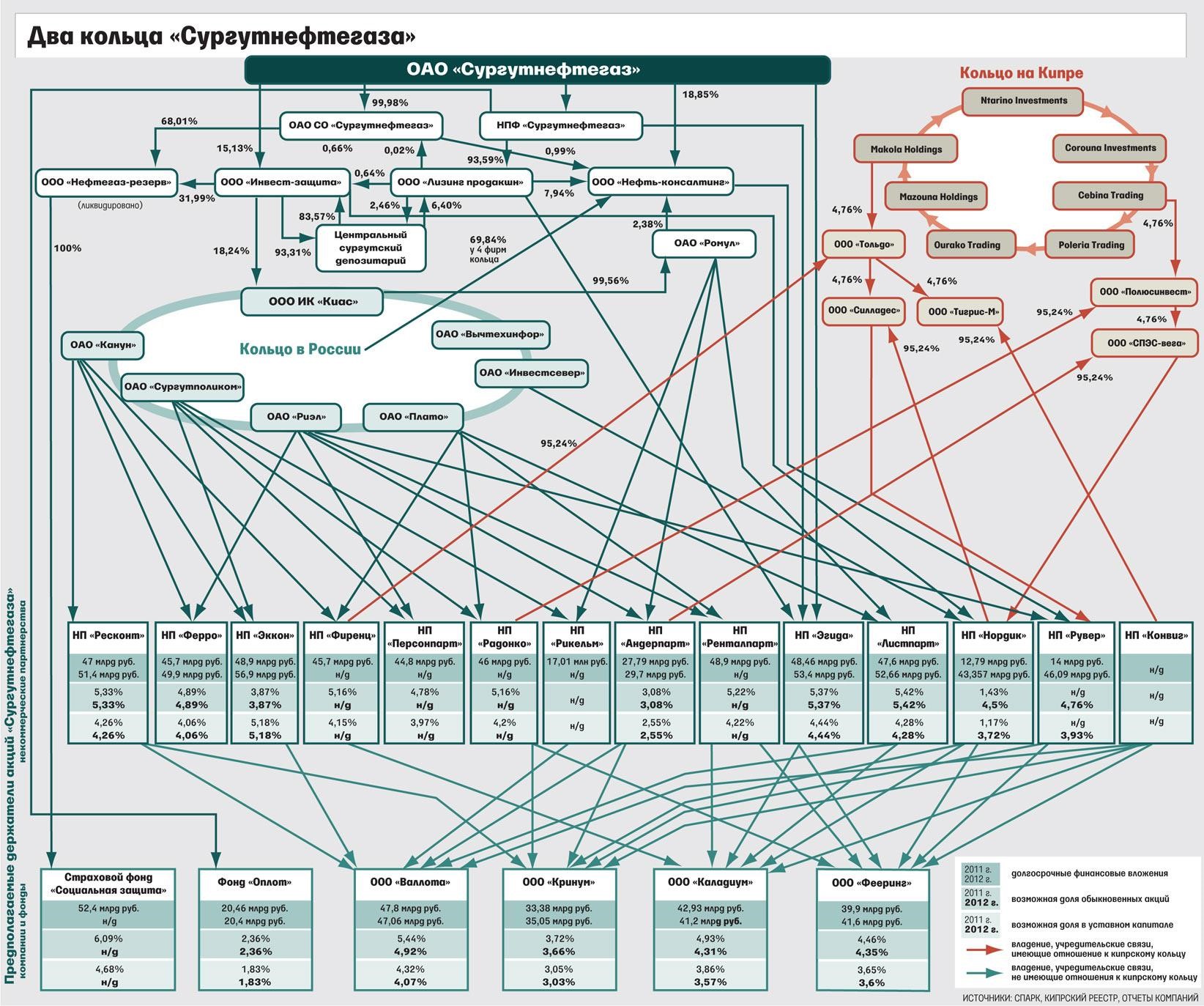

The most suspicious thing about Surgutneftegaz, which invites the most daring assumptions, is its circular ownership structure. The subsidiaries of the company hold shares of its stock, and the subsidiaries in turn belong to non-profit partnerships that own one another, so that the first company is 100 percent the owner of the second, the second fully owns the third, the third owns the fourth, and the last owns the first.

This ownership circle began to form back in the mid-90s. In 1992, Surgutneftegaz Production Association, separated from the parent Glavtyumenneftegaz Company, was a purely upstream enterprise. It was 100 percent government-owned—as were the Kirishi Oil Refinery in Leningrad Oblast, and several marketing enterprises in the northwest of the Russian Federation. All these assets were later combined into a government-owned Surgut Holding.

Then, as a result of multi-level privatization, the shares of Surgutneftegaz JSC (the upstream company) were distributed as follows: 38 percent remained with the parent Surgut Holding, 10 percent were distributed among the employees, five percent went to top managers, and the remaining 42 percent were sold at an open auction in 1993. The privatization affected Surgut Holding itself: 45 percent of it remained under the government control, 40 percent were sold to Neft Invest Company (which, as it turned out, was controlled by the management of Surgutneftegaz), seven percent was distributed among employees, and eight percent was sold at a closed auction. In November 1995, 40.12 percent of the government-owned shares were sold to the Surgutneftegaz Pension Fund, which was controlled by the upstream company.

At first glance, Surgut Holding remained the formal owner of Surgutneftegaz, controlling 38 percent of the shares accounting for 51 percent of the votes. In fact, however, Surgutneftegaz controlled about 87 percent of the shares of its parent company through affiliated structures and a stake distributed among its employees. Later, additional issues of 1996 and 1997 diluted the minority votes, which left Surgut Holding and its subsidiaries with 67 percent of the voting shares in Surgutneftegaz. In 2000, Surgutneftegaz issued 12 billion new ordinary shares and exchanged them for Surgut Holding shares, thus gaining control over 99.3 percent of its nominal owner’s stock.

The year 2003 was a milestone for the company. A few months before the attack on Yukos Oil Company, Putin traveled to the city of Surgut and had a lengthy private conversation with Surgutneftegaz CEO Vladimir Bogdanov. After that, the CEO virtually disappeared from the public eye, stopped commenting on the financial aspects of the business, and limited his statements to technology issues and production processes. Surgutneftegaz stopped disclosing its ownership structure. It did not disclose US GAAP or IFRS reports either. What snippets of news appeared thereafter were reduced to mere insider information.

For example, in 2003, the Vedomosti business newspaper reported that Surgut Holding had been transformed into a private company and renamed Leasing Production LLC. Three years later, this asset was sold, as suggested by Vedomosti, for $20 billion. The true meaning of the transaction remained a mystery, given that, until its liquidation in 2014, Leasing Production LLC had been actually controlled by the managers of Surgutneftegaz and its pension fund. Thus, it can be stated that Surgutneftegaz has become the most closed company in Russia—at the very moment when other Russian market players were switching to international reporting standards and increasing their transparency, which helped them attract investors and increase capitalization.

In 2007, Vedomosti uncovered a network of 23 legal entities—companies, non-profit partnerships and funds associated with Surgutneftegaz—either established by the company or managed by its managers. CEO Vladimir Bogdanov was on the books as the CEO of nine of them, thus directly controlling more than half of the voting shares. He later abandoned the positions in the structures of the "ring", transferring authority to his subordinates. These front-companies in total accounted for 73 percent of Surgutneftegaz shares. Some of their CEOs were also Surgutneftegaz officers. Take for example Krinum LLC, a company in the city of Surgut, founded by six non-commercial partnerships and offering the services of street cleaners. In 2013, the company had 35 billion rubles, or $1.1 billion, in long-term assets. Its CEO Olga Pustovalova, the only employee of the company, was at the same time Chief Accountant of Surgutneftegaz. In 2021, Krinum LLC had total assets of 63.2 billion rubles, and its new CEO Alexey Panteleev was also Head of Servicing Department at Surgutneftegaz.

Around 2011, the ownership “network” was expanded to include a system of Cypriot offshores, also owned by one another, and holding shares in the Russian companies that owned Surgutneftegaz and were controlled by its management. The Cyprus ring is closely interwoven in the larger network: of the six non-profit partnerships that own the mentioned Krinum LLC, five have ties with the Cypriot offshores affiliated with Surgutneftegaz.

As we see, formally, Surgutneftegaz belongs to itself and does not have ultimate beneficiaries; however, the corporation refuses to disclose them point-black, thus recognizing the existence of ultimate owners. Its 4Q 2018 report discloses only one “shareholder with at least five percent of the capital or at least five percent of ordinary shares”—the National Settlement Depository, accounting for 11 percent of ordinary and 66 percent of preferred shares. Yet, the NSD is the nominal holder of the block, not the owner.

A case in point here is the way CEO Vladimir Bogdanov reacts when asked questions about Surgutneftegaz shareholders. He coldly notes that the law does not require disclosing this information, and that he himself knows not who owns the company he has headed for more than 30 years. He explains that he only owns less than a two-percent stake, while access to this information requires owning 2.5 percent shares. It follows that Bogdanov has no idea who appoints him as CEO of the corporation. This kind of behavior (“I am but a small person, I know nothing, I just go to work, and I have never seen my bosses”) is more typical of a mafia accountant interrogated by the police than of the CEO of Russia’s third largest oil corporation.

Surgutneftegaz can kill you!

In April 2013, about 40 percent of Surgutneftegaz shares worth at least $15 billion were found to have disappeared off the balance sheet. The only possible explanation was that these shares had been sold—but to whom, and by whose decision, no one knew. There were no announcements from the management of the company, which was in the top 10 world’s oil producers. The global market was genuinely puzzled. The Financial Times wrote: "Someone should sue, but look what happened to Browder."

In 2005, British investor William Browder, owner of the Hermitage Capital investment fund, bought a minority stake in Surgutneftegaz. He then went to court to get more information about a large portion of the shares held in opaque structures, and sought to have these canceled as treasury shares. Browder revealed a scheme for selling oil through intermediary structures headed by friends of the Russian president and demanded an explanation. But he was expelled from Russia five days before his lawsuit against Surgutneftegaz was due to be heard in court. The Supreme Court rejected all of the plaintiff's claims. In 2008, Browder, who continued his investigative activities, was charged in absentia with tax evasion on an especially large scale.

Much more tragic was the fate of Sergey Magnitsky, who worked for the Firestone Duncan law firm, providing services to Hermitage Capital investment fund. On November 24, 2008, he was arrested on charges of helping the fund owner, William Browder, evade taxes. The case was brought by police Lieutenant Colonel Artyom Kuznetsov, and the investigation was led by Major Pavel Karpov. According to documents provided by Firestone Duncan management, the Kuznetsov family had spent about $3 million over 3 years, and the Karpov family had spent more than $1 million, which strongly indicated their connection to organized crime.

Sergey Magnitsky died as a result of inhuman treatment in the pre-trial detention center a week before he was supposed to go out. His death caused a wide international outcry: United States in 2012 and later Canada adopted the Magnitsky Act, introducing personal sanctions against those responsible for violating human rights and the rule of law in Russia. Earlier, in 2010, the European Parliament passed a non-binding recommendation that EU governments explore the possibility of visa and financial sanctions against individuals mentioned in documents related to the Magnitsky case. Thus, the beginning of sanctions pressure on Russia was laid even before the aggression against Ukraine.

The immediate cause of the repression against Magnitsky was the scheme uncovered by the lawyer, according to which some officials stole $230 million from the Russian budget through the Moscow Tax Service. The money went abroad, and two Federal Tax Service employees Olga Tsaryova and Elena Anisimova, who had previously bought expensive real estate in Dubai (UAE), fled there. Sergey Magnitsky, shortly before his death, established the involvement of Tsaryova and Anisimova in the theft of 5.4 billion budget funds under the tax refund scheme.

That was only one episode in the serial scheme. Novaya Gazeta journalists suggested that Anatoly Serdyukov, the former Minister of Defense, who headed the Federal Tax Service in 2004-2007, was the beneficiary of the 5.4 billion-worth embezzlement. Later, Novaya Gazeta published an item how the same schemes that Sergey Magnitsky exposed allowed the same people steal more than 11 billion rubles of budget money in 2009-2010. The stolen money was then found in various parts of the world. In 2016, some of it was found in the offshores of the cellist Roldugin, known as Putin’s childhood friend and “wallet,” that is, the holder of one of the President’s “collective funds.”

But it was the conflict between Browder and Surgutneftegaz management that started this chain of tragic events. Why was the government concerned so much about the inviolability of the secrets of a private company? The answer is obvious: the officials who could use the Russian law enforcement agencies as a tool and who controlled the Supreme Court were the beneficiaries of Surgutneftegaz. Considering the circumstances of the case, there is no doubt that the financial interests of Vladimir Putin were directly affected. That is why the corrupt law enforcement agencies reacted in such a coordinated and cruel manner.

The rising star of the Russian opposition, Alexey Navalny, who at that time led the Narod nationalist movement tried to take up the baton from Browder. In April 2008, as a minority shareholder owning 2,500 ordinary shares, he criticized Surgutneftegaz at a meeting of shareholders for its closeness and stingy dividend policy. He also demanded that the management clarify the details of murky and unprofitable schemes of oil sales through intermediaries (in particular, Gunvor, associated with President Putin's friend Gennady Timchenko) and disclose the ownership structure of the corporation. He never received any material explanations. In May 2008, he filed lawsuits with the court of the Tyumen region demanding the disclosure of the information and, predictably, suffered a complete fiasco. After the authorities started criminal prosecution against Browder and Magnitsky, Navalny lost interest in Surgutneftegaz and stopped engaging in investment activism, switching his focus to investigative journalism and publishing insider information. This ultimately landed him behind bars as a personal enemy of Putin.

Another well-known Russian prisoner, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, is certain Surgutneftegaz has also played a role in his fate. As a result of bankruptcy of Yukos Oil Company, its key asset, Yuganskneftegaz, arrested by the state, was bought at an auction in December 2004 by mysterious Baikalfinancegroup LLC for $9.3 billion, although the market price of the company was estimated at 2.5 times higher. How come a company registered just two weeks before the auction had such money?

Here are a few curious facts that may hint to the answer. Baikalfinancegroup LLC was founded by MAKoil LLC (the latter also owned the authorized capital of the former) and Reforma Company. Baikalfinancegroup CEO Valentina Davletgareyeva, a resident of the village of Dmitrovskoye, near Tver, also co-owned Sovereign Inc. and Forum-Invest, affiliated with Surgutneftegaz. Reforma belonged to KIAS Investment Company LLC, and in September 2003, Alexander Konobievsky, deputy head of the Surgutneftegaz production support base, was listed as Reforma’s CEO. The board of directors of the company also included his Surgutneftegaz colleagues Timur Arslanov, Igor Minibayev and Irina Yefimova.

According to the Vedomosti newspaper, Surgutneftegaz employees also participated directly in the auction that decided the fate of Yukos. They were Igor Minibayev, head of the department of organizational structures of Surgutneftegaz, and Valentina Komarova, first vice CFO. At the same time, the Vedomosti source emphasized that Minibayev made the only and final offer at the auction. If so, then there is every reason to believe that the purchase was paid from the famous shadow money box of Surgutneftegaz.

This deal of the century clearly shows that Surgutneftegaz neither owns the money box nor profits from it, because three days after the famous auction, which looked more like a special services operation, Baikalfinancegroup LLC was acquired by Rosneft for ... 10,000 rubles, which equaled the authorized capital of the company. Thus, the Yukos assets, with a market value of up to $25 billion at that time, were handed over to Putin's longtime friend Igor Sechin virtually for free.

The official legend says Baikalfinancegroup borrowed the money for the purchase of Yukos Oil from Rosneft itself, which in turn borrowed it from its subsidiaries, Sberbank, Vnesheconombank and the Chinese oil company Sinopec as an advance payment for future oil supplies to China. However, if so, it is completely incomprehensible why Rosneft had to expose Surgutneftegaz managers in the process. They could have taken any bum from the street to create a bogus firm. A more plausible version is that the government banks acted only as intermediaries who issued a loan to Rosneft from the funds of Bogdanov’s company, which had since 2002 started to accumulate revenues in its accounts. As for the Chinese loan, if there was one, it must have immediately migrated to one of the collective funds of Putin's criminal gang.

If that was the case, it must have created a hole in the finances of Surgutneftegaz, which was very difficult to patch quickly and seamlessly. It was not until 2011 that Rosneft was able to pay off the obligations that arose from the purchase of Yukos assets by Baikalfinancegroup. Perhaps this circumstance explains why Surgutneftegaz did not start disclosing its financial statements until 2013.

Mafia is changing the game

Numerous experts have tried and failed to find facts confirming the loud statements of political scientist Stanislav Belkovsky, who claimed that Putin personally owned 37 percent of Surgutneftegaz. Experts analyzed the company's ownership structure looking for at least some, even if indirect, connection with the president's family. When they could not find any, they disappointedly declared Belkovsky’s version a conspiracy theory.

They all made one fundamental mistake—using business analysis methods to reveal a criminal group built on a different foundation altogether. For the mafia, legal control over assets is completely irrelevant. What matters is control over owners. When racketeers daily collect 70 percent of a market stall’s proceeds, they quite sincerely consider the stall their own. They do not perceive the nominal owner as a subject, especially if for some reason the owner cannot change the “protection.” Most often, bandits do not care to participate in the operational management of the business—all the more so as they have no sufficient competence for that.

Mafiosi do not regard the owners of the businesses under their “protectorate” as a threat. What they are concerned with is other criminal groups competing for the same spheres of influence. Since Russia is a mafia-owned country, the organized criminal groups (OCGs) themselves look to the government for protection as the only way in which they can continue their illegal activities with relative impunity. In turn, the government is interested in selling protection services and trading in administrative resources, spending budget funds in the interests of mafia-controlled enterprises, and receiving “kickbacks” from them. This is how a symbiosis was born back in the 1990s between the state bureaucracy, corrupt security forces and criminal communities.

Under Putin's rule, the bureaucracy began to play a dominant role in this trio. The goodfellas (Russian “bratva”, which literally means “brothers”), the grassroots criminal groups, gradually fell out of the picture. Primarily, it happened because natural resource rent, such as oil, gas, coal, metals, etc., became the main source of enrichment for the mafia state—while in the 1990s, organized crime groups fed themselves through retail trade and power redistribution of property. Back then, a government officer needed a goodfella in order to take away the proceeds from a merchant. The redistribution of rental incomes, which started to grow rapidly in the late 1990s, no longer involved small-fry street gangs.

What was needed instead was the monopolization of government power in the hands of the mafia. The arrival of Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin marked this change. Mr Putin finally pushed aside the old Soviet party nomenklatura, personified by the Yeltsin family, and the first-wave oligarchs, who had made their fortunes on lucrative privatization of "orphaned" Soviet assets. The new mafia structure was based on the trinity of the higher bureaucracy, security officials and economic agents playing the role of collective funds. The principle of a criminal organization—gaining control over people, not over blocks of shares—became a priority, and sometimes the only thing that mattered.

It would be naive to think that Rosneft and Gazprom, controlled by Putin's friends Igor Sechin and Alexey Miller, are state-owned or commercial enterprises whose purpose is to make money for their shareholders. Their main function is serving as collective funds of the mafia that has taken control of the government. And, since the government has become an instrument of the mafia, large corporations have become instruments of the government policies, serving the interests of Putin's organized criminal group. Their formal economic indicators have long ceased to play any role. Rosneft has repeatedly been recognized the most mismanaged corporation in the world, and the extravagance of Gazprom, implementing insanely unprofitable projects for decades, has become legendary. They enrich their contractors, and the contractors deploy meaningless megaprojects to fill the collective funds of the Kremlin mafia, which controls the mining giants.

In the 1990s, the government was actively engaged in privatization—this brought about a generation of oligarchs, who were full-fledged economic and political entities. During the years of Putin's rule, priorities changed. The bloated government and quasi-government structures now generate three-quarters of the GDP, and the entire national economy works for a single beneficiary—the mafia, which controls assets formally owned by the state. The oligarchs have degraded to the level of nominal holders of collective funds. Anyone who has tried to challenge the new rules of the game have lost their statuses. Powerful oligarchs of the Yeltsin era such as Khodorkovsky, Berezovsky, and Gusinsky lost their fortunes and were forced to emigrate. Only those who managed to adapt to and accept the new rules of the game have remained afloat.

His master’s servant

Vladimir Bogdanov occupies a prominent position among the new servants of Putin's mafia. Mr Bogdanov administers the largest collective fund of Kremlin bandits, known as Surgutneftegaz. The success of this manager, who never became an oligarch, is due to the fact that his relationship with Putin's organized crime group is a model for modern Russia. The relationship had begun long before the former KGB officer and St. Petersburg mayor's office employee reigned in the Kremlin. Surgutneftegaz was the future dictator’s first major trophy, which he began to digest back in the mid-90s.

When Russian vertically integrated oil companies were forming, Surgutneftegaz received processing and marketing assets, mainly in the Leningrad Oblast and St. Petersburg: the oil refinery at Kirishi (the only in the region), the Nefto-Kombi chain of gas stations (over 100 stations in St. Petersburg), the Ruchyi oil depot (storing 70 percent of gasoline in the region), the Krasny Neftyanik oil depot (storing fuel oils), Lennefteprodukt (a network of filling stations in Leningrad Oblast), etc. The company thus became a monopolist in the regional fuel market.

However, by 1996 Surgutneftegaz had actually lost control over its subsidiaries. It was a forcible takeover, typical for the 1990s. Tax officers and the police arrived at the Ruchyi oil depot, and did not leave until the director agreed to rent the depot to the bandits for peanuts. Later, the shares of the oil depot were also handed to the raiders. In 1996, Surgutneftegaz lost its share in the city's largest gas station network Nefto-Kombi: an additional issue was announced, which diluted Surgutneftegaz’s share to a small block. The meeting of shareholders, where the decision was made, passed under the dictation of the bandits. On the morning before the meeting, strong fellas met the lawyer representative of the parent company at his front door, and carried out the appropriate “explanatory work.”

So who became the new owner of the high-margin business? In all such cases, the assets would pass under the control of the Petersburg Fuel Company (PTK, in Russian: Петербургская топливная компания, ПТК). The company was controlled by the famous Tambov organized criminal group, originating from the Russian city of Tambov. The Tambov gang was the backbone for both the criminal world of St. Petersburg and the city's economy.

The Tambov gang was created in 1988 by Vladimir Kumarin and Valery Ledovskikh, natives of Tambov. At first, the gang operated “under the wing” of the Velikolukskaya organized criminal group, but in 1991, it became independent. The gang worked on a wide range of the criminal craft: “protecting” shell game artists and brothels, extorting money from entrepreneurs, smuggling, and organizing forcible takeovers. It is noteworthy that the well-known TV journalist Aleksandr Nevzorov was engaged in advertising the group, creating the image of the most influential criminal structure in the city. Later, when Nevzorov became a State Duma Deputy, Kumarin got the position of his assistant.

After the collapse of the Velikolukskaya organized criminal group, the Tambov gang became the largest criminal community in St. Petersburg. In the mid-90s, the gang began to legalize its capital, engaging in commerce, and setting up private security companies, in which its street fighters were officially employed. The largest asset of the Tambov gang was the Petersburg Fuel Company (PTK), a monopolist in the city's fuel market. The company’s CEO was Dmitry Kumarin himself, who had by that time changed his surname to Barsukov.

One of the success factors of the Tambov group was its close relationship with the St. Petersburg mayor's office, where Vice-Governor Vladimir Putin was in charge of relations with law enforcement agencies and organized crime. At first, his personal role in the development of the group was insignificant, but as the Tambov business was legalized, he began to play an increasingly prominent role, enjoying gratitude both in the form of offerings and in the form of shares in mafia-controlled enterprises. Initially, the PTK was established by the mayor's office, and the bandits did not have a controlling stake in it. They received it with the direct assistance of Vice-Governor Putin. For his services, the new owners gave him a 50-percent share (the nominal holder was his friend and classmate Viktor Khmarin). The practice of titling assets in other people’s names was widely used by bandits. Dmitry Kumarin himself registered his stake in PTK and other assets (e.g., the five-star Grand Hotel Europe on Nevsky Prospekt) in the name of his financier Andrey Podshivalov.

In parallel, Putin helped the establishment and development of a network of enterprises controlled by his friends. Part of them were related to the sale of fuel. Whereas domestic sales were controlled by the Tambov organized crime group, the export was traditionally under the “protection” of the security forces, primarily the FSB (formerly the KGB). Putin, as a native of the secret services, had the opportunity to trade his influence and connections in both areas.

After PTK seized control of the sales assets of Surgutneftegaz, the next target was destined to be the Kirishi refinery. The ownership of the Kirishi plant was decided in 1996 at a gangster gathering. Of course, neither the official protocol nor a group photo of the participants survived. However, numerous testimonies allow us to conclude that Vladimir Putin, who was a co-owner of the Petersburg Fuel Company, was present at the meeting. He also represented the St. Petersburg mayor's office, and his friends in the KGB, who were engaged in the export of oil products. Surgutneftegaz was represented by Sergey Sobyanin, Chair of the Legislative Assembly of Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug—a well-known lobbyist for oil corporations. Since Surgutneftegaz was a key taxpayer in Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, it had to have a “protection” in the regional authorities as well.

The further course of events allows us to reconstruct the agreements reached at the meeting. The PTK renounced its claim to the Kirishi refinery in exchange for favorable terms of oil products supply. Formally, Surgutneftegaz retained control over the enterprise, but the actual beneficiary was the “rightful owner,” that is, the team of Gennady Timchenko and firms affiliated with the special services that had been protecting the plant since the late 80s, even before the government handed it over to Surgutneftegaz. Sobyanin actually signed the capitulation on behalf of Surgutneftegaz and acted as a guarantor of uninterrupted oil supplies. His mission must have also been to convince Surgutneftegaz management that being friends with the mafia was more profitable than trying to fight it.

For Sobyanin, that meeting was truly fateful. From the moment Putin came to the Kremlin, his career received a powerful impetus. He became in fact the only non-Petersburg native who entered the close circle of friends of the Russian dictator—with the exception of Sergey Shoygu, whom Putin “inherited” from the former president. Vladimir Bogdanov showed understanding and agreed to the role of a junior partner of the St. Petersburg mafia. After all, the bandits did not completely take the profits from the plant: something remained.

The team of Gennady Timchenko (nicknamed Gena the “Gangrene”) was closely associated with the special services on the one hand, and the Tambov organized criminal group and Putin on the other. He assisted Putin in the implementation of his first scam, barter supplies of food from abroad for Leningrad in exchange for duty-free sales of raw materials (oil, timber, non-ferrous and rare-earth metals) from the Russian reserves. According to the head of the commission investigating Putin's activities, Marina Salye, the deal resulted in $850 million of damage for the city.

Timchenko himself, as the Vedomosti newspaper wrote, was not a regular KGB officer—he collaborated with intelligence agencies was a continuation of his main activity. Timchenko had a day job at the USSR Ministry of Foreign Trade, under the cover of which he was engaged, among other things, in the establishment of export enterprises used to finance the needs of the KGB abroad.

In 1990, Timchenko began working for Urals Company created by the KGB and represented the company at the Kirishi refinery. In 1991 he moved to work abroad—for Urals Finland Oy. Since 1987, the export from the Kirishi plant had been concentrated in the hands of the Kirishineftekhimexport Trust (renamed Kinex in 1994). The enterprise was controlled by Timchenko and his three friends—Andrey Katkov, Yevgeny Malov and Adolf Smirnov. Adolf Smirnov was also Vice CEO of the Kirishi refinery, so business partners had no problems accessing the refinery products at "exclusive" prices. Since it was not the extraction of crude oil but the sale of petroleum products that brought money, it is clear in whose pockets the profits from the formally government-owned enterprise settled.

Kinex would take the oil products at the plant and transport them abroad, to their Finnish partner Urals Finland Oy. Apart from Timchenko, the Finnish company employed former security officers Pannikov (CEO), Tarasov, and Rovneyko. Meanwhile, the USSR collapsed, the KGB ceased to exist, and the originally KGB-established company simply passed into the hands of its managers.

The handover of the Kirishi plant to Surgutneftegaz did not change the situation—the Timchenko team continued to consider the plant their own. Kinex, which fully monopolized the exports of Surgutneftegaz, was privatized separately from the parent company. In 1994, the company came under the complete control of Timchenko and his three partners—Katkov, Malov, and Smirnov—as a result of a series of frauds, including deliberate bankruptcy. In 1995, they also acquired the Urals joint venture in Finland, renaming it International Petroleum Products. Thus, the entire chain of marketing of petroleum products abroad was in the hands of Timchenko's team.

Curiously, Kinex was at first a major player in the domestic market: it was a wholesale supplier for the PTK, and in 1999 it began trading in crude oil. At first, in 1999-2002, Kinex was only one of the intermediaries selling Surgutneftegaz oil, and not the largest one. However, unlike others, Kinex managed to buy oil at prices well below the market. William Browder in the 2000s studied customs statistics to find out that Kinex bought oil at a “discount” of $35 per metric ton (about $7 per barrel), and resold it abroad at market prices. Considering that in the early 2000s a barrel cost about $20, the intermediary acquired the oil 25 percent below the market. This simple scheme allowed Putin's friends to pump about a billion dollars out of Surgutneftegaz in 1999-2002.

This fact indirectly points to the true owner of the asset. Had Surgutneftegaz possessed even a minimum independence, it would have been extremely hard to motivate the company to such “charity”. It would have been even harder to explain it to the shareholders why the company was giving up most of its margin to an absolutely unnecessary intermediary. A completely different picture transpires if we assume that Putin's criminal group is the ultimate beneficiary of Surgutneftegaz. In this case, the predatory discount becomes reasonable, since it reduces the tax base—as a result of which only the Russian economy bears the losses. And for those who control the entire production chain, from oil extraction to refining and marketing, it does not matter at what stage of it the profit is generated, since they do not have to share it with anyone anyway.

A significant part of the money milked from Surgutneftegaz settled in Rossiya Bank, another collective fund of Putin's organized criminal group (better known as the Ozero cooperative). After the former St. Petersburg official started his career in Moscow, he gradually rose from a regional “solver” and “protector” to an authoritative mafia boss. Upon becoming president, he vigorously started to build his own business empire, relying upon a pool of friends and accomplices.

The empire grew from Surgutneftegaz, the structure Timchenko and Putin controlled the most fully. In 2002-2003, the company came under the control of the Kremlin lads. Around this time, the looped ownership structure of the company was formed, with Vladimir Bogdanov turning from its owner into a figurehead. The model of “profit privatization” was the same: the sales of Surgutneftegaz were handed over to two monopoly intermediaries, Surgutex and Gunvor. The first sold petroleum products; the second dealt with crude oil. Later, the scheme was scaled to the entire Russian oil industry, and Gunvor began selling up to 40 percent of all Russian oil.

Surgutex was established in St. Petersburg in 2002. By 2004, according to Forbes, its annual turnover had grown from zero to 360 billion rubles ($12 billion at the time). Kinex quietly sank into oblivion along with Timchenko's partners Katkov, Malov and Smirnov, who were no longer needed. Timchenko aka “Gangrene” now ran both Surgutex and Gunvor. His partner in both enterprises was one Pyotr Kolbin. The name of Kolbin is a clear indication of the person whose interests the two enterprises served.

Until 2000, Pyotr Kolbin worked as a butcher at a St. Petersburg market. The only reason why the butcher suddenly became a nominal billionaire and a shadow oligarch is his childhood friendship with the future president of Russia. That Kolbin is Putin’s confidant and “wallet” is clear, for example, from the fact that he sold (or, better to say, gifted) luxury real estate in Moscow to Anna Zatsepilina, the grandmother of Alina Kabayeva, known as Putin’s mistress. Mr Timchenko has also given similar presents to the pensioner Zatsepilina.

In 2016, Timchenko and Kolbin were added to the US sanctions list as Putin's confidants. In an interview with the BBC, US Deputy Treasury Secretary Adam Shubin said that according to the US authorities, Putin's personal money was invested in Gunvor. Naturally, the money had been taken from the notorious “collective fund”. Given that Gunvor originally developed on the basis of Surgutneftegaz, one should have no doubt—the actual beneficiary of Gunvor is the Russian dictator himself.

How to leave Putin high and dry

Surgutneftegaz has been on the US sanctions list since September 2014. In 2018, its twelve subsidiaries also came under the US sectoral sanctions. And yet, the imposed restrictions have been nominal and often random, in no way hindering the activities of the corporation. Now, American companies cannot supply Surgutneftegaz with goods and technologies for oil field development in deep waters and on the Arctic shelf, as well as in shale formations. But the corporation has never been engaged in the development of offshore or shale deposits. So what is the point of the restrictions?

In the same way, completely futile are American sanctions against the Surgutneftegaz subsidiaries: among the latter, for example, is Chervishevsky Farm, a small milk farm in the Tyumen Oblast, or Surgutmebel LLC, a manufacturer of windows, doors, furniture, and prefabricated wooden structures.

It is ridiculous to even assume that such measures will make the Kremlin change its foreign policy. Despite the sanctions, Surgutneftegaz has managed to sell oil products even to the United States, albeit in small volumes. In 2017, the company entered the markets of South America, and received about $100 million in revenue in six months. In 2020, foreign markets accounted for 77 percent of Surgutneftegaz's revenue. These facts demonstrate that sanctions from the global community have done little to stop the company from earning billions for Putin.

A really effective blow to the Kremlin would be adding to the list all the entities associated with the Russian mafia’s largest collective fund, including offshore companies. Other smart steps would be freezing Surgutneftegaz's financial holdings, 90 percent of which are denominated in US dollars, and adopting restrictive measures against banks providing deposits to the company. This way, Surgutneftegaz would no longer be able to conduct foreign economic activity and replenish the Kremlin's piggy bank.

The freezing of Surgutneftegaz money box would be especially painful for Putin and members of his criminal group. A series of pinpoint strikes against Surgutneftegaz would have a great demotivating effect on the Russian ruling elite and the private business associated with it. Imposing sanctions on a dairy farm owned by the oil corporation is one thing (the cows will not stop giving milk, right?). Having the mafia’s savings worth tens of billions of dollars cancelled at a moment’s notice—is absolutely different. It would be hard to find a more effective humiliation for Putin than exposing him to his inner circle as a naked king.

A. Kungurov. Pfoto: RBK